“At any given time, there’s five million kids playing baseball in the United States and only a half million in high school and only 50,000 in college,” Murphy said, “About 5,000 make the pros, and only 700 get to the big leagues.”

Sean Murphy, Mike’s son, defied those odds by not only getting to the highest level of baseball — he’s the first Centerville High School graduate ever to do so — but by thriving there.

Sean made his big-league debut for the Oakland Athletics on Sept. 4, 2019, and hit a home run in his second at-bat. He hit .245 with four home runs in 20 games last season. This season, Murphy hit .233 with seven home runs, starting 39 games at catcher.

In the postseason, Murphy has stepped up his game. He hit a solo home run in Game 3 of the wild-card series as the A’s eliminated the Chicago White Sox with a 6-4 victory Thursday. On Monday, in Game 1 of their American League Division Series against the Houston Astros, Murphy hit a two-run home run in a 10-5 loss.

Through Monday, Murphy had started all four playoff games for the A’s and was hitting .308 (4-for-13) with two walks. He had one hit in each game.

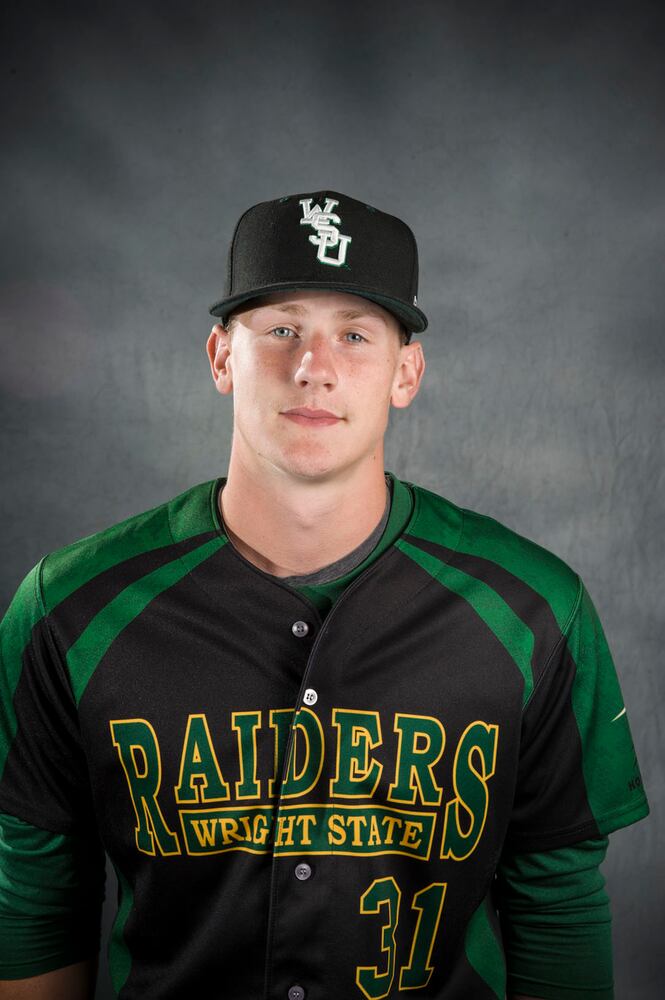

All of this is thrilling for Murphy’s parents, Mike and Marge, and everyone who watched his rise at Centerville High School and then Wright State University — and none of it is surprising. From the beginning, even though he was a late bloomer physically, Murphy has had the skills, the intelligence and the work ethic to overcome the odds and become a big leaguer.

“Baseball’s been in our family a long time,” Mike said. “Sean’s taken it to a much higher level than anybody in our family has ever done. It’s been quite the experience.”

Credit: Barbara Perenic

Credit: Barbara Perenic

Player coach

Sean was born in Peekskill, N.Y., in 1994. The family moved to Centerville in 1998. Mike and Marge are both engineers. They came to the area for jobs and currently run Acadia Lead Management Services in Dayton.

Even as a kid, Sean had his eyes on a life in baseball. When Sean was about 4½ years old, during the middle of the famous home run chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, Marge asked him what he wanted to do when he grew up.

“I want to be Mark McGwire,” Sean told her.

“You can’t be Mark McGwire,” Marge said, “but you could be like Mark McGwire.”

That story is indicative of Sean’s drive, his dad said Monday, but to make the dream real, he had to love the game, and by the time he arrived at Centerville High School, it was obvious to everyone how much he did.

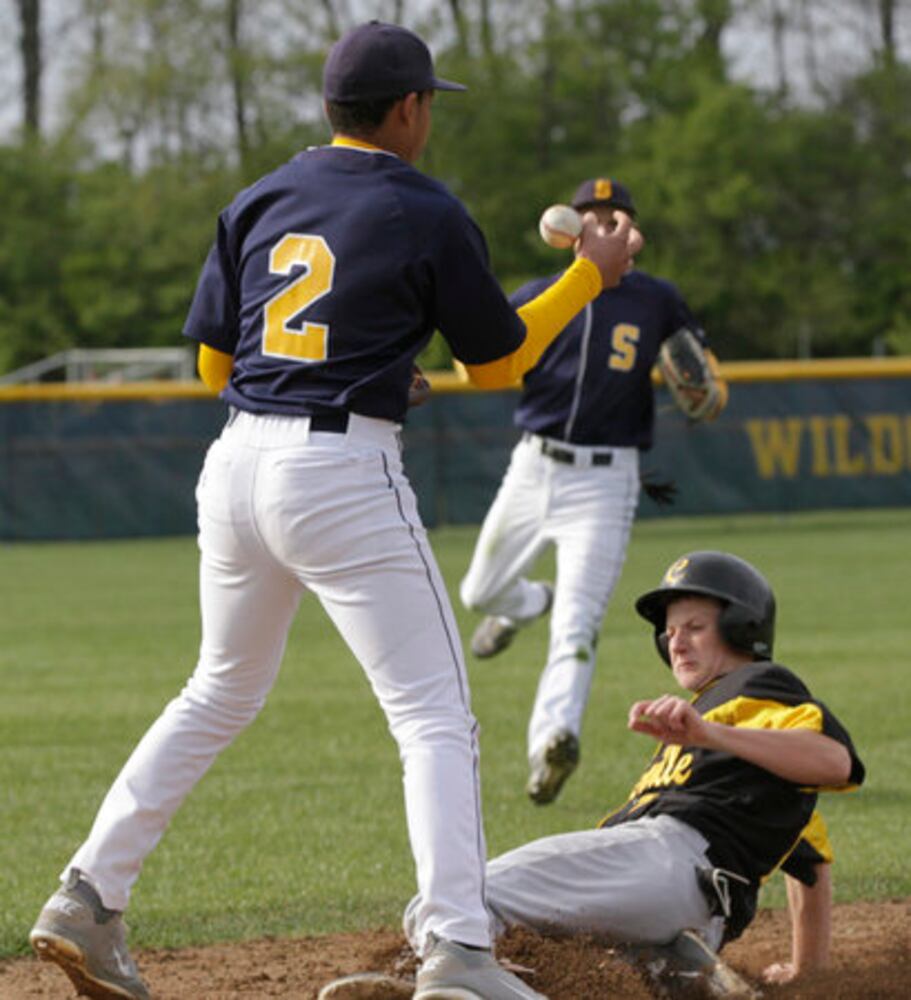

Jason Whited, the current head coach at Centerville, was an assistant to Terry Dickten during Murphy’s high school years. Sean played on the junior varsity team as a freshman, which is rare at Centerville, and made the jump to varsity as a sophomore, another rare feat at the school, though he didn’t get many at-bats.

As a junior in 2012, Murphy hit .373. A year later, as a senior, he hit .541. At the same time, he was like a coach on the field for Dickten and Whitehead and for all his teammates. Everyone raves about his baseball IQ.

“I could be pitching to him,” former Centerville teammate Ryan Fox said, “and I’d throw a bad pitch, and he’d yell out that my front side is flying open. He was making pitching adjustments for me, and he was always right. You could always trust whatever Sean told you. I always looked up to him.”

Overlooked prospect

As good as Murphy was, a flood of scholarship offers didn’t come because of his size. He was 5-foot-9 and 145 pounds as a junior. His dad was a late bloomer who grew 4½ inches and put on 50 pounds after high school.

That growth pattern was there, Mike Murphy said, but there were no guarantees. Wright State was the only Division I program willing to give a chance.

“Sean first showed up to my catching camp in ninth grade,” said former Wright State coach Greg Lovelady, now the head coach at Central Florida. “He could always catch, but the size was concerning. His mom’s petite. His dad is huge. So you’re trying to decipher it. That’s part of the recruiting process. We were all very hesitant. He didn’t get recruited very much.”

Lovelady was a walk-on himself in college at the University of Miami and played for two national championship teams. He sold Murphy on the walk-on opportunity being a solid one. At that point, Murphy had already hit another growth spurt, reaching 5-11 by the time he started college.

“I don’t think we ever said, ‘Hey, this guy is going to be 6-3,’” Lovelady said, “but he was so cerebral and so smart, that we knew he was going to bring something to the table. In the worst-case scenario, he was going to be our defensive catcher.”

Murphy grew another two inches in the 10 months after arriving at Wright State and added more height in the following year, ending up with the 6-3 frame he has now.

“You could really see things were starting to come together,” Lovelady said.

Murphy hit .302 with four home runs and 34 RBIs as a freshman in 2014 — Wright State made him a scholarship player after that season — and .329 with four home runs and 36 RBIs as a sophomore. He hit .226 with three home runs and nine RBIs in the Cape Cod League in the summer of 2015. He was named the 10th-best prospect in the league.

“Going to the Cape, seeing what that looked like, gave him the confidence that he belonged,” Lovelady said. “Every year, you just saw the growth in terms of the confidence. He belonged in the national conversation.”

The next March, however, a broken hand cost him a large chunk of the season. He returned after missing a month and hit .287 with six home runs and 34 RBIs. The injury may have prevented him from being drafted in the first round. The A’s selected him in the third round.

“I remember telling all the scouts, you don’t want to miss on him,” Lovelady said. “I still can’t believe he went in the third round. I thought he should have been a first-rounder.”

Credit: Thearon W. Henderson

Credit: Thearon W. Henderson

Memorable debut

Murphy hit .267 with 34 home runs in four seasons in the minors before getting to the big leagues near the end of the 2019 season. He was on the roster for the first time on Sept. 1 when the A’s were playing at Yankee Stadium. That was a thrill for his dad, who’s from the Bronx.

Three days later, Mike and the rest of the family, including Marge and Sean’s older sister, Erin Geyer and her husband Branden, and Sean’s fiancee Carleigh Green, were all in the stands in Oakland to see Sean make his debut.

“When that lineup was posted that day, which is like three hours before game time, that’s when the butterflies set in,” Mike said. “It became very surreal for mom and dad. I texted him before the game to tell him to just take a moment to think about what you’ve done during a quiet time during the national anthem. Realize you’re standing on a Major League Baseball field. Very few people have done that.”

Mike wasn’t nervous watching Sean catch because he knew that’s his calling hard. It’s the at-bats that make him nervous. He knows how hard hitting is.

The first-bat Sean looked nervous, Mike said, and he struck out. The next-bat, he was locked in, and the result was a home run. The cameras caught the family’s reaction and focused on Mike’s emotions.

“I watched the ball leave the bat,” Mike said. “I had the right angle. We were on the third-base side. I saw the trajectory of the ball. I knew it was going to split the gap. I had no idea it was going to clear the fence. It was more of a line drive than a moon shot. My wife was already jumping up and down. As soon as I knew it had cleared the ball, I lost my mind.”

Giving back

More success has followed that first game. Murphy started the wild-card game last season, but the A’s lost 5-1 to the Tampa Bay Rays. He has been the full-time starter this season. Through it all, he has been the same guy everyone remembers at Centerville and Wright State.

“He was so quiet, so nice, so humble, so mature and right from the jump,” Wright State Athletic Director Bob Grant said. “He just sort of had the air of a pro right from day one. He’s the quiet guy who exudes confidence but has an awesome humbleness.”

Murphy comes back to visit the current Raiders, Grant said, just like veteran pitcher Joe Smith. They both have their names on a new sign outside Nischwitz Stadium. It lists all the players who have been drafted out of Wright State.

Murphy also gives back at Centerville High School by visiting often.

“He comes to all of our camps,” Whited said. “I’ll reach out and say, ‘Can you speak to our kids?’ He donates baseballs. He comes to our youth sessions. It’s usually a very quiet message. It’s just about loving and enjoying the game. He always deflects praise.”

Whited said Murphy has always been that way. He’s never heard anyone say anything negative about Murphy. He’s just loved by everyone.

Last spring, when baseball was shut down by the coronavirus pandemic, Whited threw batting practice to Murphy three or four times at Oak Grove Park on Social Row Road in Centerville. Whited planned to see him play in person this year, but that idea was put on hold because fans were allowed to attend games.

Like Lovelady in Florida, Fox in California and Murphy’s parents in Ohio, Whited watches every Murphy at-bat on TV. Sean’s fiancee, who he’s marrying in November, got to see the wild-card series games in person in Oakland but can’t attend the games this week at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles.

Baseball will allow fans to attend the World Series, so there’s a chance Murphy’s family will get to see him play in person this season. Until then, they will cheer from afar.

“The world kind of stops when the baseball game’s on,” Mike said.

About the Author